Romeo and Juliet is, and seemingly always has been, a story of young love and not much else. In that sense, Romeo is a Dead Man is inadvertently pointed in its adaptation of Shakespeare’s most popular work. Of course, it isn’t a literal translation of the original story about warring families in Verona; it just similarly struggles to arrive at a meaningful point. What the game does do is frame its Romeo’s star-crossed pursuit of his Juliet through a most strange and unusual spacetime, delivering a satisfying, albeit outdated, brand of hack-and-slash action. This is Romeo is a Dead Man.

“O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?”

The story of Romeo Stargazer, which begins with space-time being torn asunder and Romeo being left for dead, only to be brought back from the brink by his eccentric time-travelling grandpa, Benjamin Stargazer, is an insane trip through the stars. Romeo quickly joins the ranks of the FBI’s Space-time Police. He is tasked with exploring the galaxy, trawling singularities, and pruning the timeline of self-serving criminals who’ve taken advantage of the space-time fracture. He mixes business with pleasure, to a degree, using his space-hopping resources to search for his missing girlfriend, Juliet, who continues to manifest as malformations and show ties to the destruction of the timeline itself.

If it sounds bonkers, it’s because it is, and it plumbs depths of obscurity that I feel like only the likes of Suda51 can. To say I managed to follow the game’s events would be overstating things. The story baffled me right through to its epilogue, which took everything weird I’d already seen, ratcheted it up to eleven, and left me straddling the edge of madness as I scrambled to piece it all together. Romeo is a Dead Man, as confusing as it is, is a wildly entertaining romp through the city of Deadford’s past, present, and future as Romeo is put through the ringer saving the world one calamity at a time.

As a relative stranger to Suda’s other works, it’s hard for me to draw comparisons to the likes of Killer is Dead or No More Heroes. There’s a quirky, dated appeal to the gameplay in Romeo is a Dead Man that, quite unlike its titular hero, cements it in a certain place and time. It reminds me more of old Devil May Cry than new, with its threadbare combat mechanics doing little to one-up its modern contemporaries. What Romeo has in spades, however, is style. In fact, it has lakes of it, whereas its combat feels no deeper than a puddle. Aside from a bevy of spectacular boss fights, which certainly can demand a modicum of concentration from the player, the general undead you’ll face moment-to-moment pose little threat.

“These violent delights have violent ends, and in their triumph die, like fire and powder”

With Romeo’s kit a veritable godsend from his saviour grandfather, the Deadgear and its toys do encourage a bit of flair within the battlefield. I expect the designer believed that the quick exchanges between melee and ranged combat might make for a frenetic, breathless tussle; however, there’s an unshakeable sluggishness that comes with taking out Romeo’s firearm. For a game that places value on moving, pivoting to a near standstill to aim robs encounters of their seamlessness and reactivity. Despite the game’s allowance to have you hot swap mid-fight, of the four swords and four guns available, I’d eventually settle down with my favourites and find quite enough joy in slicing things to bits.

Outside of a pretty simple mix of attacks, both light and heavy, and dodges, Romeo’s Bloody Summer special attack is the player’s most powerful source of offense. It’s a bankable, if upgraded, kaleidoscopic flurry, a culmination of your combat prowess, and a spectacular means of dispatching crowds or dealing decent damage to bosses. Romeo can also call upon his homegrown Bastards, his own little army of undead who’ll help in battle; depending on the seed planted, they come out with all manner of skills and can add a bit of flair to proceedings.

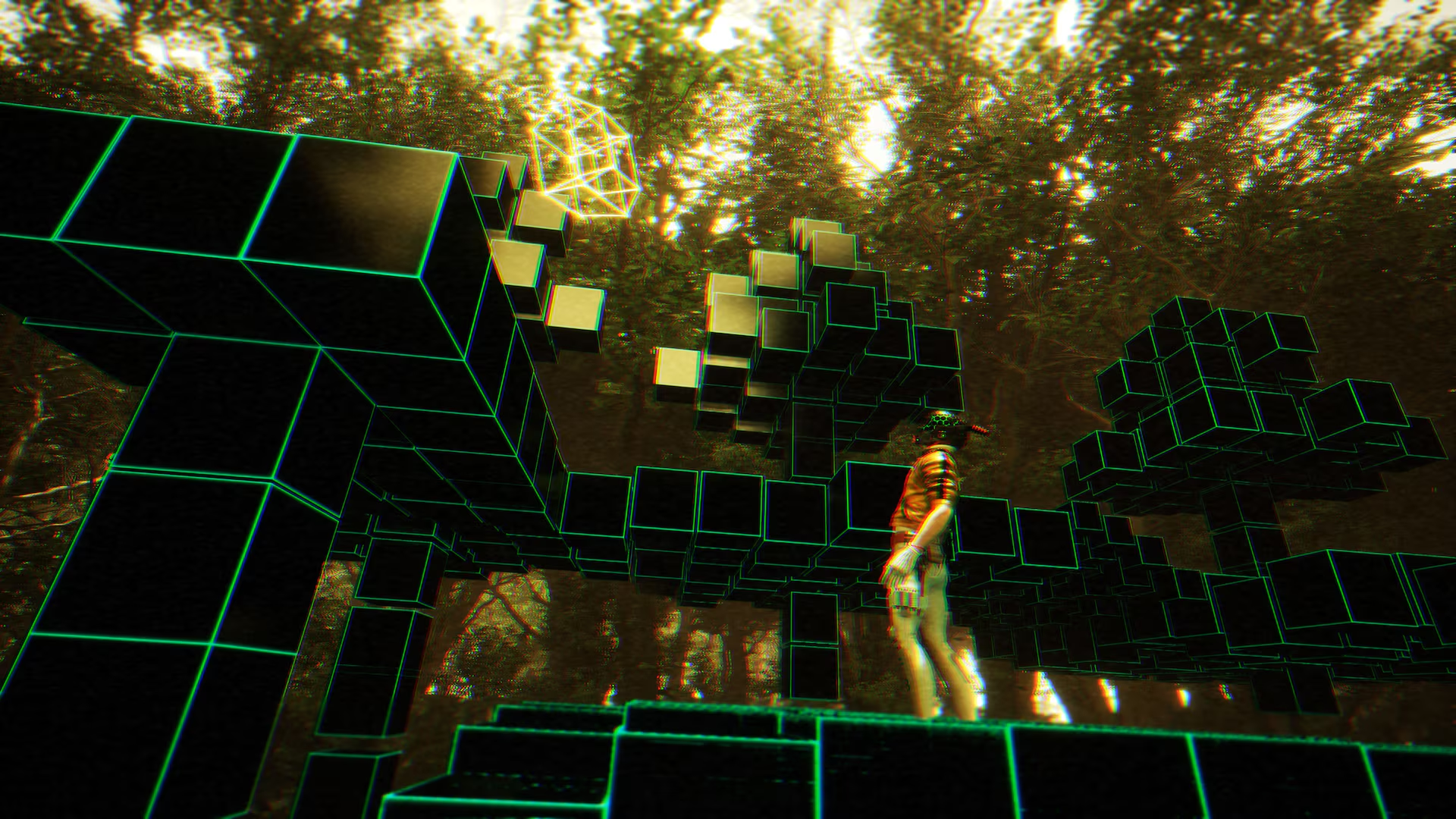

With the story jumping all over the place, Romeo’s adventure takes us to a heap of different places to unravel these space-time knots. From forests to city halls to asylums, the game moves along at a pretty quick clip, never eager to settle in one place. What’s learned before long is that each of these linear spaces has an inverse subspace that Romeo can explore to clear paths forward in real space, from behind the curtain, so to speak. Each stage follows the same formula, with the action being frequently halted in favour of these stark, almost digital, mirrorscapes where the guns are holstered in favour of light puzzle-solving and platforming. Despite their intriguing role in the overarching narrative, I didn’t care at all for the subspace areas. Having to take pause every ten minutes, just as the action would crescendo in a fight worth having, was a frequent source of disappointment.

“A plague o’ both your houses!”

Romeo’s home between missions is The Last Night, the FBI’s Space-time Police headquarters ship. It has quite literally everything Romeo could need before, during, or after a mission, as the ship can be used as a refuge between boss attempts to upgrade skills, check your Bastard crops, or cook a curry or two. Unlike the standard action, the ship’s interior transforms into a pixel-art space; it feels like entering another world entirely, but it’s a relatively cost-effective way to have the game’s cast of secondary characters, all seemingly displaced from their own times, put to screen. Mini-games serve as the facade for many of Romeo’s upgrade and crafting systems, although they’re pretty basic. Cooking is a simple timing exercise, while buffing Romeo’s respective stats is tucked behind quasi-Snake, which is fuelled by one of the game’s very few currencies. As an experience beyond the action, it’s kept rather uncomplicated and lean.

While exploring the fragment universe, you’re able to visit small space-time tears that house desirable materials to assist in Romeo’s growth. Like the game itself, which presents its difficulty options in a rather Forrest Gumpian way, in that they’re different flavours within the box of chocolates that is life, there are a few tiers of challenge to be found within these mini-dungeons. On the whole, sadly, they’re rather repetitive and, once you’re adequately levelled and in the late-game, I didn’t feel that the juice was worth the squeeze in terms of rewards.

Romeo is a Dead Man’s biggest triumph comes by way of its art and audio design, which so often feels uncanny and at odds with the game’s genre. The game finds so many means of delivering its story, whether it’s through simple comic book panels, fun pre-rendered cutscenes, or through song, with the game having a surprising amount of original tunes that serve as the backdrop for certain bosses. Even outside of these, the game’s soundtrack matches the rest of the game’s freak by deftly and effortlessly leaping from acid jazz to rock, to elevator music. I admire the lengths the developer went to in subverting expectation time, and again, it helped buoy the entire Romeo experience and helped it ascend a little higher than its other aspects should have let it. To help illustrate how on-point the design choices were in this game, I’ve got to declare Romeo is a Dead Man’s chapter title cards the coolest I’ve seen in a video game; even if the game, on console at least, struggled to render them without becoming a slideshow.

In fact, the game’s performance was constantly mired by bouts of frame loss and general sluggishness. It wasn’t consistent; it didn’t always impact the action; however, when it did, it was generally when the screen’s population was getting up there. It screams poor optimisation to me, although it’s easy to explain in-game as Romeo’s flashy finishing moves further breaking the space-time continuum so that’s perhaps a stroke of good fortune for the team. I expect it’s only a patch away from being seamless, but there’s certainly work to do pre-launch.

“That which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet.”

Romeo is a Dead Man, I feel, is a tremendous example of style being enough to shoulder the burden that comes with a lack of substance. So much of the game’s action, along with its systems, feels antiquated enough that it shouldn’t be memorable at all. Yet with innovative art direction, a Suda-typical contrast of ideas, and unconventional, albeit confusing, story craft, Romeo is a Dead Man’s style proves irresistible. When it comes to the story of this Romeo and his Juliet, as with all titles that come out of Grasshopper Manufacture, it’s more about these ultraviolent delights than the usual kind.

Review Code by the publisher

Romeo Is A Dead Man

Played on

Xbox Series X

PROS

- A creative off-kilter premise

- Incredible art direction and style

- Constantly subverts expectations and delivers on trademark strangeness

CONS

- Combat systems feel a little dated

- Subspace areas are a little bland and, too often, disrupt the action

- The narrative thread was hard to follow

- Performance pre-launch is remarkably poor at times